Vastey accuses Petion and his followers of treason for these deals! Unsurprisingly, Vastey also writes about the ex-colonist lobby in the French government, and the ill-informed, racist French news, which sought to paint Haitians as savages and push France to go to war (11). Basically, fake journalism and interests of ex-planters portraying Christophe's rule in negative light have led to Vastey's essay, which begins the first chapter explaining the background to the Haitian Revolution and why Haitians sought independence. His basic statements on Saint Domingue are brief but accurate. In fact, 20th and 21st century accounts of the preamble to the Haitian Revolution sound much like this account. Here is an example of Vastey's succinct description of colonial society from page 17:

Oge and Chavanne are given their due for helping to ignite the Haitian Revolution, the exploitation and manipulation of black and colored generals and warriors for France, Spain, and used by France against each other (Toussaint Louverture and Rigaud, the latter encouraged by Hedouville). He's also critical of Toussaint for only nearly declaring the independence of Saint Domingue, as well as some harsh words for the south of Haiti for so easily accepting Napoleon's troops on page 27:

Apparently Toussaint's brother, Paul surrendered the Spanish-speaking portion of the island to the French without a fight, falling prey to the ideas of Bishop Mauviel and Kerverseau (28). On the issue of color and divisions among generals during the Haitian Revolution, on page 39 Vastey clearly leans toward the Black Generals, who he claims never fell for the lies of the whites as much as the men of color:

Such statements add needed nuance to claims about race and color in Haitian identity, since Vastey, a member of the mixed-race ancien libre, who studied in France, so strongly identified with Christophe and 'black' generals. Subsequently, the chapter on Dessalines defends the leader as favorably disposed toward men of color (45):

Unfortunately for Dessalines and Haiti, Vastey writes that by placing his capital not in Port-au-Prince, Dessalines was less cautious of the south and west of the country, and therefore more suspectible to defeat in civil wars or coups (45). He also admits the glaring contradictions of the emperor's constitution, and states that it was pardonable given the youth of the nation, suggesting in retrospect that a constitutional monarchy would have been better (47). Vastey's hositility toward Petion, a traitor to the Haitian cause, is seemingly justified if Vastey is correct to note that Petion plotted with Haitians from abroad (who were allowed to return by Dessalines) to make Petion the head of government (49). Petion's role in assassinating Dessalines, a man who fully trusted him, is beyond disgusting. To quote Vastey, "Thus did Petion accomplish the destruction of his Sovereign, his friend and benefactor, in order to seize the reins of government, and kindle anew the flames of civil war" (56). He also provides an excellent character analysis with obvious bias in the fourth chapter:

(58)

(58)

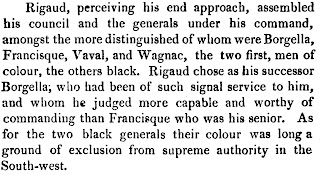

The rest of the text focuses on the various civil wars and conflicts, such as that of Goman versus Petion, Christophe and the North versus Petion's South, Goman's relationship with Rigaud (his godfather), and hurls criticism toward reductionist stereotypes of the color complex in Haitian society (93). There's also room for criticism of Rigaud's regime in the South-west:

Meanwhile, Christophe saw to the uplift, safety, and governance of the North ofHaiti while Petion engaged in battles and political conflict with Rigaud and others (100). He goes on to defend the monarchical form of government, and how representative constitutional monarchies can evade tyrants (he cites the example of Robespierre for an example of how a republican form of government can turn tyrannical, 106). In addition, the reality of French plots against Haiti does seem to be a constant presence in the writings of Vastey, even if an actual French military invasion was unlikely and too costly for France in the first decades of the century. After several pages of descriptions of the conflicts between the warring generals and officials, Vastey drops an appropriate, 'Afrocentric' claim on p. 137:

The rest of the essay merely argues over and over again how Petion fomented civil war and disunity among Haitians, was a savage, ruthless and ineffective ruler who faced an assassination attempt. His pseudo-republican title combined with despotic rule are also up for criticism to Vastey (205). Ultimately, his criticism of Petion and even Boyer near the end for succeeding like Roman emperors through the Praetorian Guard, endeavors to vindicate the state of Christophe as a better representative of Haitian independence, liberty, and black progress through schools, constitutional monarchy that is stable, and a strong stance on resisting French plots against Haitian sovereignty and freedom. Whether or not one believes all of Vastey's critiques is another question, since, like the apologists of Petion's regime, he was expected to paint Christophe and the North in a positive light. Unfortunately for this significant figure in Haitian intellectual thought and political writings, Vastey found his end in a rather nasty way after Christophe's death and Boyer's regime, which carried on the practices of Petion while closing down Christophe's schools. But the overall message of the text is that the causes of the civil wars of Haiti in this period were due to French white interference and manipulation, men of color such as Petion or Rigaud willingly making or negotiating deals against Haitian independence and black generals, and their despotic, exclusivist rule that led to further conflict along color and ideological lines. Based on what happened after Petion's death and the regressive rule of Boyer for over 20 years, one definitely sides with Vastey in some ways.

Overall, two very good posts from a bright and conscientious student, your parents must be proud. Your research taught this old man a few facts he wasn't aware of. My main problem with your writing is the question I usually ask my self after reading one of your posts. Why is he doing this, what is he trying to find in the data? " Whether or not one believes all of Vastey's critiques is another question, since, like the apologists of Petion's regime, he was expected to paint Christophe and the North in a positive light." Until I pointed out to you the distortions in the depictions of Christophe as this mad tyrant you showed not a hint of the skepticism displayed here Why is that? I don't blame you because a thorough job of distorting the past was done. It was illegal to even mention the name of Dessalines after his murder. I hope you'll do a post summing up what you've learned from reading about this period. I provided you some information on Christophe's wife and daughters in the Boyer comment thread, did you find it useful?

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading. My main purpose in writing all of this is to prepare for a potential dissertation in a few years. Of course, the writing style on this blog and inconsistent citation styles will have to be changed, but I like to think of this blog as public notes on various sources and topics that could be very useful for future research. To be honest, I must learn to read French, since without it I am dependent on English translations and secondary sources. Until then, I am going to keep writing posts about various subjects, summarizing arguments and stories and making a few of my own points or observations. I am still unsure as to which period I would prefer to focus on so I might jump all over the place. My next post I want to do is about the Piquets and the Army of Sufferers ("negro communists" to one observor from Europe)

DeleteI was not too skeptical until the end of the post. I thought the book was a overly long diatribe against Petion, which is understandable since they were fighting a civil war at times and he believed Petion was willing to sacrifice Haitian liberty. Each side in this period is very biased and far from objective (White abolitionists, white pro-slavery French and other Europeans and colonialists, Petion's republic, Christophe's kingdom). so it's difficult to say with certainty how this all played out without reading several additional sources from this period. And yes, I should do a summary post of this period, if I could figure out a way to do it succinctly, hahaha!

I remember you gave one example of how Christophe's daughters were written about but I'll check again. Vastey alluded to the Queen as a model of feminine virtue and motherliness, and that's pretty much about it. It's way to hard to find sources in the written record that reveal much of anything about women in this period, just as Mimi Sheller noted in her "Sword-Bearing Citizens," which is a very redundant essay but interesting for tackling the question of gender.

Apparently "The Colonial System Unveiled" by Vastey will be translated and published in English in 2013 or 2014 (probably the latter), so as soon as I can get my hands on that, I will try to read it. I think in that text Vastey makes more interesting commentary on colonialism that really predicts a lot of the conflicts of post-colonial states in the 20th century. Marlene Daut clearly thinks very highly of him, and she may be involved with the process.

DeleteHave you read the Memoire of Boisrond Tonnere? I came across a French copy, but, well, you know that doesn't do much for me...

I probably will have to drop any real focus on gender, given the sparse and incomplete sources. I too was wondering what happened to the comment on the Martin post. I didn't delete your comment and am perplexed as well. Maybe I accidentally did something that removed it, but I don't understand how that would happen.

ReplyDelete