Another word we find interesting in the language of the island of Haiti, given by Oviedo as a synonym for bohio, or house, is eracra. To some scholars, this sounds like a word derived from a non-Taino language spoken on the island of Hispaniola in pre-Columbian times. While this is possible, we found a potentially similar word that provides clues to its meaning. In this case, Kalinago, according to Breton's dictionary, contains the word écra, denoting bed. The resemblance to eracra could be a coincidence, but it is certainly plausible for the word for bed in Kalinago and Taino to have been similar. Interestingly, this word has not survived in Garifuna, which uses the word gabana. We couldn't find any similar word for house or bed in other languages like Palikur or Wayuu. While some scholars argue that the word eracra may come from the Ciguayo tongue, the existence of a similar word in Kalinago could point to a deeper antiquity or wider spread of it across the Antilles. Alternatively, checking Pelleprat's Galibi dictionary revealed the word acado for bed (and bati as another word for bed). We suspect eracra in Taino signified bed.

Saturday, November 30, 2024

Friday, November 29, 2024

Africa Mokili Mobimba Updated

Thursday, November 28, 2024

On Nur Alkali and the Sayfawa Dynasty

Muhammad Nur Alkali's Kanem-Borno Under the Sayfawa: A study of Origin, Growth and Collapse of a Dynasty is a vastly important work in the history of one of Africa's greatest royal dynasties. Existing for probably over 1000 years, the dynasty succeeded to build a strong state in an environmentally challenged zone. Later, they survived disintegrating forces to reemerge from their new, more secure base, Borno, as the dominant power of the Central Sudan. It's rulers were renowned for undertaking the pilgrimage to Mecca, sponsoring Islamic scholarship, and for occupying a central role in trans-Saharan and Sudanic trade routes for centuries. Nur Alkali's careful history of the dynasty, which benefits from his local connections and familiarity with Kanuri language and unpublished sources by local Borno scholars, is mainly marred by poor editing. This, sadly, occasionally hinders understanding and is a shame. Nur Alkali's explanation for the Sayfawa dynasty's decline in the 18th century is also unconvincing or incomplete. The spread of Sufism within the state, for instance, is never elucidated, and the reader is still somewhat confused about the author's argument for the growing autonomy of provinces and territorial chiefs within the Empire. Nonetheless, this work, despite its age as a 1970s dissertation, is foundational for its delicate balance of written and oral sources, plus Nur Alkali's judicious analysis of these sources to create a complete narrative of the Sayfawa maiwa.

One of the best features of the book, although also depressing, is the reference to unpublished and important studies by local Borno intellectuals. For instance, Ibrahim Imam was the author of an unpublished work, Peoples of Bornu, that is cited repeatedly by Alkali. It is a pity the work was never published since its author was a Kanuri person with elite connections who interviewed people from different backgrounds/social classes about history, genealogies, etc. While colonial-era administrators like Palmer did similar things, Palmer lacked the deeper familiarity and experience with the local languages and cultures and undoubtedly introduced his own colonialist and racist biases. Alkali also cites some other unpublished works, including ones from an elder shaykh's family library, Sheikh Abubakar El-Miskin. Obviously, we lack the ability to read such texts in Arabic, Kanuri or West African languages, but it is a shame some of these texts were never published or translated into English and French. For instance, an important Kitab by Muhammad Yanbu remains unpublished, while a study and translation of another of his texts remains inaccessible. These sources are of great importance for shedding light on local traditions of historiography and scholarship, which may be at risk of loss due to the ravages of time.

Moving on to Alkali's analysis of Kanem, or the first phase in the Sayfawa's history, our historian favors environmental/ecological understandings for the decline of Sayfawa power in the 1200s and 1300s. He also favored a divine kingship model for the pre-Islamic Sayfawa rulers, although "sacral" rather than divine kingship might be more applicable in this context. And despite the conversion to Islam, there was continuity in the "sacral" nature of kingship that was promoted further by Islamic study, pilgrimage, and devotion after Islamization of the dynasty. Nonetheless, the Sayfawa were able to unite various clans and establish a firm power base in Kanem. Through control of Kawar and trans-Saharan trade, plus ties to Egypt and the East, Kanem emerged as a major power in the Central Sudan during its Kanem phase. However, the apogee of medieval Kanem was quickly followed by decline after the reign of Dunama Dibalemi. Nur Alkali here prefers environmentalist explanations that center on the growing competition for increasingly scare resources. Imperial overexpansion under Dunama plus the decline of conditions in Kanem caused by the increasingly arid conditions led to conflict, civil strife, rebellious princes, and the near-disintegration of the empire. Nur Alkali is probably on firm ground here, as studies by subsequent researchers have pointed to dry periods and the further desiccation of the Sahel that must have contributed to the decline of living conditions in Kanem as sedentary agriculturalists and nomadic groups completed for resources. The reference to Muhammad Yanbu attributing the opening of the Mune by Dunama to the nefarious influence of Egyptians is also fascinating, although possibly a tradition from centuries later that did not accurately reflect what transpired. Nonetheless, that later generations of Borno scholars believed Egyptian intervention may have played a role in the destabilizing of Kanem suggests the Sayfawa maiwa may have been seen as a potential threat by leading powers of the Muslim East.

Miraculously, however, the Sayfawa dynasty survived the century or so of political instability and strife after Dunama Dibalemi's reign. The houses of Idris and Dawud battling for the throne, scheming kaigamas and wars or battles with the Bulala, Sao (spelled Sau by Nur Alkali) and Judham Arabs did not lead to the complete collapse of the dynasty. Yet, realizing how unsustainable Kanem was and the ongoing conflict with the Bulala, the Sayfawa wisely made the decision to relocate to Borno as the center of the Empire. According to Nur Alkali, Borno was an excellent choice for rebuilding the Sayfawa state. Here, in a rich agricultural plain favorably situated for trade with both North Africa and across the Sudanic belt, the Sayfawa were able to reestablish their power through a period of consolidation, expansion and, in the 18th century, decline. Borno, whose "Sao" and other non-Kanuri groups were not completely subjugated until the reign of Idris b. Ali in the late 1500s, was nonetheless a favorable environment for agriculture, leather, textiles, salt trade, the slave trade, and the growth of towns and cities, like Birni Gazargamo. Borno, in short, provided a firmer foundation for the next apogee of the Sayfawa dynasty, one built on a more stable base that did not quickly collapse as the case of Kanem.

As one would expect, much of the book is spent on the important reigns of mais like Ali Gaji, Idris b. Ali, Umar b. Idris, and Ali b. Umar as major figures in the development of Sayfawa's power. These rulers also exemplified certain trends of state-building and political philosophy that reflected Islamic influences as well as local factors deeply rooted in the dynasty. Unlike Nur Alkali, we would suggest the Sayfawa retained many aspects of their pre-Islamic roots, particularly those which enhanced the status of the mai. Yet, under the periods of expansion and consolidation in the 1500s and 1600s, Borno embraced new ideas, military tactics and weaponry (firearms, for instance), and administrative reforms to integrate non-Kanuri peoples into the state. This remarkable achievement led to a period of longer-lasting hegemony and regional preeminence for Borno, which saw its influence spread deeply across the Central Sudan and the effective reconquest of Kanem, it's ancient heartland. Rulers like Umar b. Idris appear to have strengthened or consolidated the gains of the 16th century by incorporating, as in the case of Muniyo, a Mandara prince as a loyal agent of the state. Additional provincial officials were appointed and incorporated into a complex administrative system that improved defenses while preserving a predominant role of the central state for ensuring additional military support in the provinces.That said, one is surprised by some of Nur Alkali's conclusions. For instance, he expressed skepticism about the presence of Turkish mercenary gunners in the army of Idris b. Ali during the 1570s. That struck us as an unfair conclusion, particularly as Ahmad b. Furtu would have been well-informed and certainly able to distinguish Turks, Arabs, and others. In addition, some of Idris b. Ali's campaigns in and near Borno itself were not mentioned, since the author focused on the campaigns against the Sao and Ngizim. That seems to have been a mistake, since understanding Borno's relations with the Tuareg in the 1600s and 1700s would have benefitted from an analysis of Tuareg groups raiding Borno's frontier in the 1500s. This was clearly a longstanding problem in the region, and almost certainly one in which the sultans at Agades likely had little or no control over.

As previously mentioned, we are not sure his explanation for the decline of the Sayfawa in the 1700s is convincing or complete. The period of decline, which he states began as early as the late 17th century but really developed over the course of the 18th, was attributed to a gradual loss of Sayfawa or Central control of territorial chiefs and rulers, like the Galtima (galadima?). This process is not exactly clear, although this may reflect our limited sources on this era. It is clear that some provincial officials began to ignore the Mai in Gazargamo while other peoples, like the Bade, resumed their semi-autonomous state. Meanwhile, the conflicts with the Tuareg did not end, as Borno lost, in c.1759, the lucrative Saharan site of Bilma. In addition, a drought in the 1740s triggered more southward migration of nomadic groups like the Tubu, Koyam and Jotko, who were not easily controlled by the Sayfawa. Unfortunately, we are still in the dark about why exactly the central government began to lose control of provincial chiefs and officials. And why this process led to a decline in military effectiveness that would be necessary to reassert Sayfawa control. Was it due to an abandonment of an expansionist foreign policy? In a disappointing way, Nur Alkali's final chapters seem to echo the problematic views of Urvoy, who see in the Late Sayfawa Period a series of weak rulers more focused on Islamic piety and study than the ordeals of effective state management or policy. Of course, this portrayal could be accurate, but it seems quite incomplete and does not adequately explain why the administrative system of fiefs, territorial divisions and military defenses severely declined across the 18th century. Undoubtedly, the famine years were likely an important factor. Tuareg raids and the loss of Bilma certainly contributed, too. But something else must have been occurring during the "Late Sayfawa Period" to hasten this decline. This decline, perhaps best epitomized by Mai Ali's disastrous 1781 campaign against Mandara, revealed just how much decay or rot infested the state. References to written sources seem to affirm this idea of corruption and decay, too, if the poems of al-Tahir (died c.1776) and other intellectuals are any indication. But surely there remains much room in future scholarship to entangle what caused the decline of the Sayfawa political system in the 18th century.

To conclude his study, Nur Alkali briefly elucidates the rise of conflicts with the Fulani in western and southern Borno as well as the rise of al-Kanemi (though quite briefly). We are in complete agreement with Nur Alkali on the primarily political nature of the conflict with the Fulani, rather than religious factors being important for understanding Borno's conflicts with Sokoto. We also find it unlikely that Muhammad Bello's account is very reliable, although he should still be seriously considered in light of local Borno sources referring to corruption and internal problems in Borno during the 18th century. But one was hoping for a history of the Sayfawa that chronicled their later years of decline, as al-Kanemi increasingly sidelined them and became the effective head of government. What was the Sayfawa court like in those days, as it was reduced to figurehead status and dependence on al-Kanemi for its very survival of the Fulani attacks? One suspects that those depressing twilight years from c.1808-1846 involved factors that might have been unsavory to elites of Borno in the 20th century. Yet understanding those crucial decades might elucidate our struggle to make sense of the pre-Shehu years of Borno and why, according to Barth and others, records of the Sayfawa dynasty may have been destroyed or obfuscated. That complex, ambivalent legacy seems very relevant for an understanding of the historiography of Borno and how one dynasty supplanted and later erased the one whose very existence had been central in the history of Kanem and Borno. Although it does appear that many notables from the Sayfawa period were incorporated into the al-Kanemi dynasty's system, which inherited and maintained many aspects of the previous system, there likely were a series of conflicts over power and legacy which shaped how the history of the Sayfawa is remembered in the 20th and 21st centuries.

In summation, Nur Alkali's study is a major one that highlights a number of local sources, traditions, and perspectives on one of the world's great royal dynasties. While the explanatory power of the later chapters on Borno's decline leave something to be desired, this is an excellent overview of the complex history of a major dynasty. The familiar problems of sources is a huge barrier for the early period in the dynasty's history, before Islamization in the late 11th century. Nonetheless, Nur Alkali adroitly draws from oral traditions and written sources to develop a plausible model for the Sayfawa dynasty's rise and fall in Kanem. While we take issue with the portrayal of the pre-Hume Mais as divine kings, his analysis of Kanem's decline after its zenith under Dunama Dibalemi is persuasive. Today, with the benefits of more archaeological excavations and new interpretations of the old sources, one can undeniably improve upon this. But, one should pursue the theory proposed by Muhammad Yanbu on Egyptian interference influencing Dunama Dibalemi's behavior with regard to the Mune. Likewise, scholars today must reexamine the 18th century in Borno, trying to find and publish any texts from that era and studying family papers, manuscripts, and texts that have survived. Lastly, a serious analysis of the role of slavery and the slave trade in the history of Kanem-Borno is a must. Nur Alkali largely ignores slavery, though sources suggest captives were the most valued commodity of the Sayfawa state in trans-Saharan commerce. Local agriculture, textiles, leather products, and salt were probably of greater importance for sources of revenue and in terms of the state's trade with other Sudanic peoples (Hausaland, Kwararafa, Kanem, Bagirmi, etc.), but slave labor contributed to this to some degree. While probably on a smaller scale than the prevalent system of slavery in the 19th century Sokoto Caliphate, any attempt at developing a deeper understanding of the social and economic history of Kanem-Borno must treat the issue of slavery more deeply.

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

"Bambara" Timeline

Adanson's augmented/revised map includes the "Bambara Empire" of which he knew little except for its role in providing slaves.

-c.1137: al-Zuhri writes of Ghana attacking "Barabara" people for slaves, as well as Tadmakka raids against the "Barbara" pagans. The description of al-Zuhri is quite ambiguous, but the "Barbara" appear to have been pagan peoples related to the peoples of Ghana and to have practiced facial scarification and believed in their own nobility.

-1464-65: Sonni Ali of Songhay defeats Mossi ruler, Komdao, pursuing him to limits of "Bambara' land (Tarikh al-Fattash)

-c.1506: Earliest written attestation of "Bambara" in the Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis, a work referencing Banbarranaa, Beetu and Bahaa as towns whose inhabitants travel to Toom to buy gold for slaves. Mandingua merchants buy gold in the fairs there.

-c.1558: Askia Dawud of Songhay, in addressing the ruler of Jenne, alludes to Bambara incursions.

-after 1591: Pagan "Bambara" referenced as attacking Jenne after the fall of Songhay (Tarikh al-Sudan).

-c.1593-1608-1615: Ahmad Baba of Timbuktu, in his response to the questions of al-Isi on who was permissible to enslave, mentions the Bambara and Bobo as pagans beyond Jenne. A Bambara presence in Kala is also mentioned. The Bambara may also have been referenced as the pagan population living closest to the lands of Islam.

-1597-98: Pagan Bambara referenced in the Tarikh al-Sudan as allies of Hammad Amina, ruler of Masina

-1599: Mansa Mahmud IV of Mali fails to take Jenne

-1644: Revolt of Bambara of Segu area (Abitbol), possibly the revolt against the Sanakoi and Farkakoi

-c.1650: Traditions indicate Bamana presence in Segu by 1650

-1674: Arma expedition against Bambara in Bara

-Late 1600s: Kaladian Koulibaly active as leader.

-c.1712-1755: Reign of Biton Koulibaly at Segu

-c.1715: Ruler of Cheibi fled to Douko, Bambara town, to escape an attack from the Pasha of Timbuktu

-1716: "Bambara" soldiers in Timbuktu

-1716-1719: Military expeditions against Bara Bambara from Arma of Timbuktu

-by 1719: "Bambara" slaves in Jacmel Quartier of Saint-Domingue (if not present earlier)

-1728: Labat describes people of Bambara as slaves of their king

-1731: Conflict between Haoussa and Gourma and Bambara pagans; Samba Rebellion in Louisiana, led by a "Bambara" slave

-1733: Askia el-Hadj aids son of Maro to defeat Silti-Ouerendagh, pagan Bambara

-1739: Calm for all Bambara from Dirma to Bara and Bara to the west; reports of Fa Maghan the Wangara attacking Jenne and Bambara tradition of Fa Maghan attacking Segu and his defeat (Chronicles of Gonja)

-1740s: Long drought that severely impacted the Sahel region of West Africa

-c.1742: Pasha Said attacks 11 Bambara towns or settlements near the town of Askia El-Hadj

-1747: Ighor, a "Bambari," attacked caravan of Alid Oualata, taking prisoners.

-1753-1754: Segu blocked town of Sansa, Masina, and killed its chief, Folokoro

-1754-55: Segu attempts to take Jenne

-1755: Death of Biton Kulibali

-1756-57: Murder of Doukoure, son of Biton Kulibali, by slaves of Biton; Segu ruler who attempted to impose Islam deposed (faama Ali)

-1757: Adanson's Histoire naturelle du Sénégal: coquillages refers to the "Bambara Empire" that provided captives sold at Galam and the Gambia.

-1758-59: Death of Kedebo Kanimou, ruler of Segu, after Tames. Succeeded by Kafa Dyogui, 3rd slave to govern Segu after death of Biton Kulibali.

-1766: Ngolo Dyara seizes power in Segu (reigns 16-18 years)

-1775-76: One of slave leaders of Biton Kulibali pillaged town of Hammat

-1788: Jacques Jacquet, dit Bambara, free black near Mirebalais (Saint-Domingue) appears as owner of runaway slave

-1790: Death of Ngolo Dyara, Reign of Da Manzon begins

-before 1791: a "Bambara camp" or neighborhood of Port-Louis in Mauritius established

-1796: Segu attacks Kaarta; Mungo Park visits Segu

-c.1806: Death of Gilles Bambara, a leader in the Haitian Revolution imprisoned by Dessalines for bring up "caste" (the color question).

-1812: Muhammad Bello of Sokoto writes of the Bambara land as one rich in gold and inhabited by pagans

Sources

Abitbol, Michel. Tombouctou Et Les Arma: De La Conquête Marocaine Du Soudan Nigérien En 1591 à L'hégémonie De L'empire Peulh Du Macina En 1833. Paris: G.-P. Maisonneuve et Larose, 1979.

Amselle, Jean-Loup, and Elikia M'Bokolo. Au Cœur De L'ethnie: Ethnies, Tribalisme Et État En Afrique. Paris: Découverte, 1985.

Caron, Peter. 1997. “‘Of a Nation Which the Others Do Not Understand’: Bambara Slaves and African Ethnicity in Colonial Louisiana, 1718–60.” Slavery & Abolition 18 (1): 98–121. doi:10.1080/01440399708575205.

Clozel, F.-J. (François-Joseph), and Maurice Delafosse. Haut--Sénégal--Niger (Soudan Franc̜ais): Séries D'etudes Pub. Sous La Direction De M. Le Gouverneur Clozel .. Paris: E. Larose, 1912.

Courlander, Harold, and Ousmane Sako. The Heart of the Ngoni: Heroes of the African Kingdom of Segu. 1st pbk. ed. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994.

Geggus, David. "The French Slave Trade: An Overview." The William and Mary Quarterly 58, no. 1 (2001): 119-38. Accessed October 3, 2020. doi:10.2307/2674421.

Gomez, Michael A. African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

Green, Toby. A Fistful of Shells: West Africa from the Rise of the Slave Trade to the Age of Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

Hopkins, J. F. P., and Nehemia Levtzion. Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West African History. 1st Markus Weiner Publishers ed. Princeton [N.J.]: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2000.

Houdas, Octave Victor. 1901. Tedzkiret En-Nisian Fi Akhbar Molouk Es-Soudan. Paris: E. Loroux.

Levtzion, Nehemia. Ancient Ghana and Mali. New York, N.Y.: Africana Pub. Company, 1980.

Maghīlī, Muḥammad ibn ʻAbd al-Karīm, and John O. Hunwick. Sharīʻa in Songhay: The Replies of Al-Maghīlī to the Questions of Askia Al-Ḥājj Muḥammad. London ; New York: Published for the British Academy by Oxford University Press, 1985.

Marty, Paul (trans.). 1927. Les Chroniques de Oualata et de Nema (Soudan Francais). Paris: Paul Geuthner.

Monteil, Charles. Les Bambara Du Ségou Et Du Kaarta: (Étude Historique, Ethnographique Et Littéraire D'une Peuplade Du Soudan Française). Paris: É. Larose, 1923.

Moreau de Saint-Méry, Méderic Louis Élie. Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie françoise de l'isle Saint-Domingue. 3 vols. Philadelphia: 1797.

Richard, François G., and Kevin C. MacDonald (editors). Ethnic Ambiguity and the African Past: Materiality, History, and the Shaping of Cultural Identities. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, Inc., 2015.

Roberts, Richard L. Warriors, Merchants, and Slaves: The State and the Economy in the Middle Niger Valley, 1700-1914. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1987.

Saʻdī, ʻAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʻAbd Allāh, and John O. Hunwick. Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Saʻdi's Taʼrikh Al-Sudan Down to 1613 and Other Contemporary Documents. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 1999.

Timbuktī, Maḥmūd Kutī ibn Mutawakkil Kutī, Christopher Wise, and Hala Abu Taleb. Taʼrīkh Al Fattāsh =: The Timbuktu Chronicles, 1493-1599: English Translation of the Original Works in Arabic By Al Hajj Mahmud Kati. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 2011.

Tuesday, November 26, 2024

Mozambiques and East Africans in Colonial Haiti

Monday, November 25, 2024

Jacmel and the Slave Trade

Sunday, November 24, 2024

Pierre Cange

Saturday, November 23, 2024

Jacques of the Mamou Nation

Friday, November 22, 2024

Gnawa Bambara

An interesting fusion of jazz with Gnawa music, and named in honor of the Bambara!

Thursday, November 21, 2024

Guatiao, mi hermano

Another surprise, although it probably shouldn't be, is the use of a word akin to guatiao in the Kalinago tongue. In Breton's dictionary, it is rendered as Itignaom, quite distinct form the Galibi banaré in Pelleprat's dictionary. Clearly, Itignaom is etymologically related to guatiao, and how the word was used by the Kalinago who traded with the French may give us an idea of how it worked. The system of ritual kinship and alliance cemented by an exchange of names was used by the Kalinago and the French for trading purposes. If the Kalinago equivalent was similar to the Taino version, then the appearance of the name Agueybana in both Saona, eastern Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico could possibly have been through a ritual kinship sealed by the exchange of names. This would have facilitated trade and alliances and perhaps explain a lot of the similarities in ritual iconography, art, and even the exchange of areitos between indigenous groups in Puerto Rico and eastern Hispaniola.

Wednesday, November 20, 2024

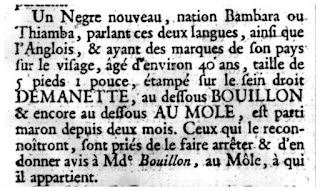

Bambara Runaways in Saint-Domingue

Another ad for a runaway includes someone who spoke both Bambara and Thiamba. If Thiamba referred to the broader cluster of Gur peoples, then it is possible this man spoke Mandingue or Bambara.

Madagascar and Haiti

Tuesday, November 19, 2024

Areito in the Batey

In order to continue our exploration of possible origins and alternative meanings of well-known words from the Taino lexicon, we decided to continue our journey with areito and batey. Both words are connected, as the batey has been conceived of as a central place or plaza in which areitos were likely conducted or held while the same space was also used for the ballgame. Therefore, exploring the etymology and development of these words may be useful for understanding the origins of three central components of "Taino" civilization in the prehispanic Greater Antilles. Relying on our usual dictionaries of Warao, Lokono/Arawak, Palikur, Kalinago, Wayuu and Garifuna, we decided to see what looking for similar words and concepts in other languages may reveal.

First, batey. This word does not seem to have close equivalents in other languages besides Kalinago. In Palikur, wetri or higiw can signify place. In Warao, a Spanish-Warao handbook gave us auti autu as en todo el centro. Plaza in Warao is jojonoko or kotubunoko, neither one sounding anything like batey. Lokono doesn't give many clues, either. Central is rendered as anakubo. A Garifuna trilingual dictionary provides amidani for middle. We must look to other languages to see possible ideas on the origins of the word.

It is only in Kalinago where a word sounding somewhat close to batey can be found. In this case, a 17th century French-Kalinago dictionary of Breton uses the word bati to designate the place or corner of someone, as in the space used by someone to hang their hammock in the house. This very specific and limited meaning suggests batey in Taino may have once held a similar meaning for a small corner or space used by someone. Somehow, over time, Taino speakers began to expand their definition of the term to encompass larger plazas or central spaces (as well as retaining the original, restricted use of it, as its survival in Caribbean Spanish attests). Interestingly, the Kalinago used the word bouellelebou to designate a yard or the place between the carbet and houses. The word they used for the place where cabins or homes were established was bouleletebou, clearly related to their word for yard. It seems likely that the Taino batey originally referred to a smaller area or space associated with a particular person, then was expanded upon to designate a larger central plaza (and the associated ballgame). It was possibly also a local development and not particularly influenced by plazas or the ballgame in Mesoamerica, if the linguistic evidence is clear.

Areíto likewise presents a challenge. In Warao, dokotu warakitane or dokoto wara mean to sing. A party is oriwaka. In Wayuu, to sing is ee'irajaa and party is mi'raa. In this same tongue, to remember is so too aa'in. None of these words are particularly close to the Taino word. Neither does Palikur come close, except for one word. However, in that language, musique is arigman. To play an instrument is arigha. More intriguingly, the word for rumor is aritka. This could actually be etymologically linked to the Taino word in the sense of rumor being related to story, storytelling, and narratives. This is also linked to the Garifuna words for remember and remembrance. Indeed, in Garifuna, a trilingual dictionary renders remember as aritagua. Remembrance is aritahani. This is close to the Taino word and the Palikur aritka. Thus, areíto, though accompanied by music and dance, was etymologically related to remembrance, history, tradition and stories. This sense is very clear in some of the Spanish chronicles. Indeed, Oviedo explicitly compared the Taino way of recording history to romances in Spain. It also makes it quite clear that a clear historical component was central to the areíto.

Surprisingly, however, the Kalinago language, at least based on the 17th century French dictionary did not possess such a close equivalent. Nonetheless, the word for storyteller, arianga-lougouti and the word for to speak, arianga, may be related to the Garifuna terms for remember and remembrance. It is also possible that speakers of Taino who fled to the Lesser Antilles during and after the Spanish conquest introduced their version of the word? But, the fact that a similar word was present in Palikur, in South America, suggests that this was not necessary for all 3 languages to develop similar-sounding words for related concepts.

So, what does this foray in language tell us? It establishes quite clearly a historical character for the areíto. The Spanish chronicles are reliable here in describing it as one whose central purpose was linked to history, or at least a "Taino" conception of history and genealogies. The word must have held deep roots and was clearly linked to historical narratives, myths, legends, and tales of lineage (for those of chiefly rank?) that were accompanied by song and dance, possibly to facilitate memory as well as entertain. The batey, on the other hand, seems to have originally designated just a small space, corner, or area of a particular person, which was presumably linked to the idea of a "yard" near their home. This was, at some later date, expanded to refer to larger central plazas and the ballgame. The antiquity of large plazas in the Caribbean suggests that this may have happened much earlier in the history of the language, and part of the reason why it didn't use words of continental origin for the space.

Monday, November 18, 2024

Inca Civilization in Cuzco

This is probably not the best place to start with for Zuidema. A translation of lecture series from the 1980s he gave in France, the book attempts to analyze myths reported in the chronicle, fieldwork based on the ceque system, and kinship structure theories to make sense of how Inca civilization in Cuzco was tied to the calendrical, agricultural, and ritual cycle. Somehow it's all connected to moieties in which, however, each ruling Inca did not have a panaca that continued after his death. I'm still not sure what to make of Zuidema, but I'm definitely in favor of the more historicist approaches to the chronicles. Zuidema, on the other hand, seems to think that viewing more of the information recorded in the chronicles as myth can actually free our minds to develop alternative models which might be closer to the realities of pre-Hispanic Andean civilization. He even compares the age-class system of the Inca to the Ge peoples of Brazil, raising a possible area of exploration by looking at the Andean age-grade system in comparison with all of South America's Amerindian peoples.

I guess I keep falling back on the historicist bias since some of the chroniclers, like Sarmiento de Gamboa, even had representatives of each 'panaca' listen to the chronicle and offer feedback for any points they disagreed with. It's possible that each group had its own 'mythohistoric' view of their collective past and were able to agree on a coherent enough vision that was written down by Sarmiento de Gamboa. But I suspect the Inca, at least since Pachacuti, had a keen interest in history in both our "modern" sense and one related to myth. I don't think they interpreted their past as entirely "mythohistoric" and the evidence of possible quipu "records" and specialists in the interpretation of said records undoubtedly meant that a core "historic" tradition must have been propagated since at least Pachachuti in the 1400s.

Sunday, November 17, 2024

A Correction...

Saturday, November 16, 2024

The Hausa in the Saint Domingue Press

Although it mainly provides limited information, consulting Saint Domingue's newspaper, Affiches américaines, available at the Digital Library of the Caribbean, is a wondrous resource. One can see advertisements for the sale of imported slaves, runaway slave notices, and, occasionally, individuals selling slaves. Sometimes the level of detail on the captive African population can be very meaningful or relevant for gaining more insight on their origins, experiences, and exploitation. Perusing it for references to the Hausa in Saint Domingue was actually quite illustrative of certain trends and theories about the Central Sudan's involvement in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade before the 19th century.

For example, one can find references to Hausa runaways that may bear African names. This above example, Boupa (Bouba?) is ambiguous, but could point to possible backgrounds for captives from northern areas who reached the Slave Coast.

Some of the advertisements for newly arrived ships carrying captives are similarly worthwhile. The example from above, from 1787, reveals that the cargo included Hausa as well as Arada captives. Intriguingly, Hausa captives had been imported since at least the 1760s, but it seems like the diverse "nations" from the Bight of Benin only began to be distinguished more regularly by the last 20-30 years of colonial rule. One wonders if the French slave traders, who probably had little ability to demand only specific "nations" when waiting to fill their cargos for the Atlantic voyage, were responding to growing demand and stereotypes of Saint Domingue slaveholders.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)